CannabisAlia Haju/Reuters

CannabisAlia Haju/Reuters

The global "war on drugs" has harmed people. This phrase,

which wouldn't have been out of place coming from the mouths of

idealistic teenagers and ageing hippies, has now found its way into the

report of a commission set up by The Lancet medical journal and Johns

Hopkins University in the US.

To say there has been a sea change in how academia and policy wonks view the "war on drugs" is an understatement, and this report is a sign of the times – calling for complete decriminalisation of drug use.

The report hopes to convince the UN to consider putting

public health at the centre of its drug policy when the issue comes up

for debate during a special session from 19-21 April. Even the cultural

legacy of the "war on drugs" is being assailed, as new revelations

reveal it was instigated by President Nixon chiefly as a weapon to use

against his opponents: minorities and the anti-war left, via Harper's Magazine.

Marijuana has often been the poster-child of drugs reform, with people generally more accepting

of its legalisation than that of other banned substances. In fact, some

local and national governments have already taken the leap towards

legalisation, such as Portugal's radical decriminalisation, and well-known drug-use havens such as Amsterdam.

Even the birthplace of the "war on drugs" has seen legalisation

efforts, with Colorado and Washington State both allowing for

recreational marijuana use.

A march in Brasilia calling for the legalisation of cannabis

ReutersFurthermore, the cause has been aided by compelling arguments about its use to treat chronic pain in people who are not only genuinely in need, but are also often as far removed from the stereotypical image of a "pothead" as possible.

With increasing legalisation, cannabis presents a potential public health problem that must be considered. Studies that followed a cohort from birth to their mid-20s have shown that use of cannabis, especially during adolescence, increases your chances of developing schizophrenia, with some estimates saying smokers are as much as two times as likely to develop the condition. It is important to put these figures into context – while on an individual level this may not represent much of a concern (after all, 2 x 1% is still only 2%), consider it at an epidemiological level.

Mental health services that are already stretched to the point of breaking may yet be put under more strain. Cannabis-using patients with psychosis require extra costly hospital visits and up to 35 additional days in inpatient care. Not only is this a problem for a cash-strapped health service but it ignores the theoretical concern of creating new patients with schizophrenia. This underscores the need for research into cannabis use, but a major problem remains: what exactly are people even smoking?

Confiscated bags of cannabis seized in the Belgian capital Brussels in 2007

GettyNow it's all done locally by guys with names like Kev and Dave, in ignored parts of city centres. The Kevs and Daves of this world have figured out how to siphon off electricity and looked up articles on websites about growing marijuana (all easily found on search engines). While they may not be as glamorous as their forebears, they understand the drugs scene is a buyer's market and they know how to compete with each other. Over the years they have altered the drug to be more potent. They also embraced marketing, with names such as Blue Dream, Sour Diesel, Green Crack and Amnesia. Simply put, this isn't the weed your parents, or maybe even your grandparents, smoked.

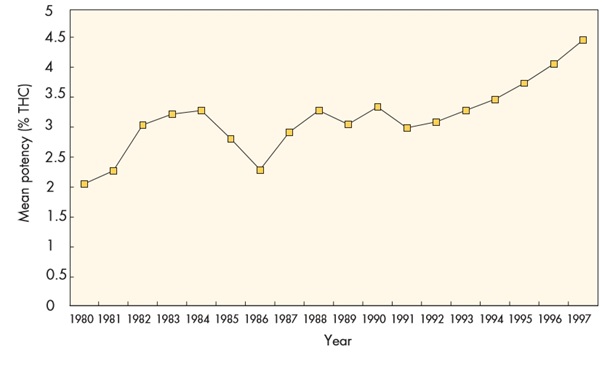

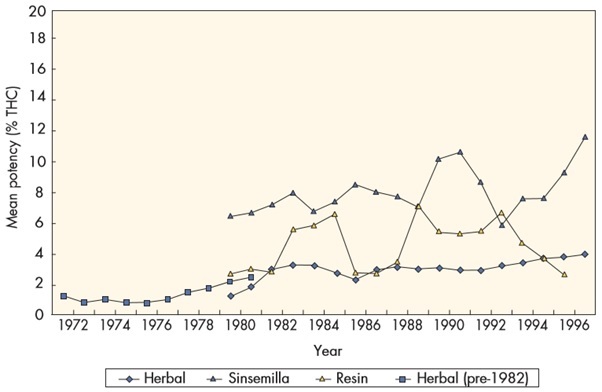

To understand the shifting landscape of cannabis use, it is important to identify its key element tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). This drug produces the sought-after effects of cannabis and is, to some extent, counterbalanced by the presence of cannabidiol (CBD). However, the rate of THC in cannabis products has been steadily increasing (see figure one) and varies from product to product (see figure two) (15).

Figure one: Mean potency of THC in cannabis in the US market. Via European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction

James Lee

Figure two: Mean THC potency of cannabis products. Via European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction

James LeeWhen given in an acute dose under lab conditions, THC alone has been shown to induce psychosis-like symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions. It also causes problems in cognition, such as memory and attention, which are similar to those in schizophrenia. Interestingly, a likewise acute dose of CBD seems to counteract this effect and is actually being considered as a treatment for non-drug induced psychosis.

This all paints a complex picture for researchers and people developing social policy. While cannabis represents a potential health problem in some areas it can also provide new insights into conditions such as schizophrenia, which has seen treatment options stagnate in recent decades.

As we consider decriminalisation, it is more and more

important that we ask what are people taking (resin, oil, herbal or some

combination of all), what is in it (THC content vs CBD content) and how

they are consuming it (smoking, with tobacco, or eating, etc.)? Only

once we understand what and how people are consuming cannabis can we ask

meaningful questions about their consequences and potential benefits.

Research is currently under way to investigate cannabis

use as outlined through this article via online surveys. If you, or

someone you know, would be interested in contributing to this research

please look at the following survey: surveymonkey.co.uk/r/the-cannabis-survey

James Lee is a PHD student at the University of

Roehampton's Department of Psychology. He is working on a neuroimaging

project to investigate the effects of long-term cannabis use on brain

function, chemistry and volume.

Post a Comment